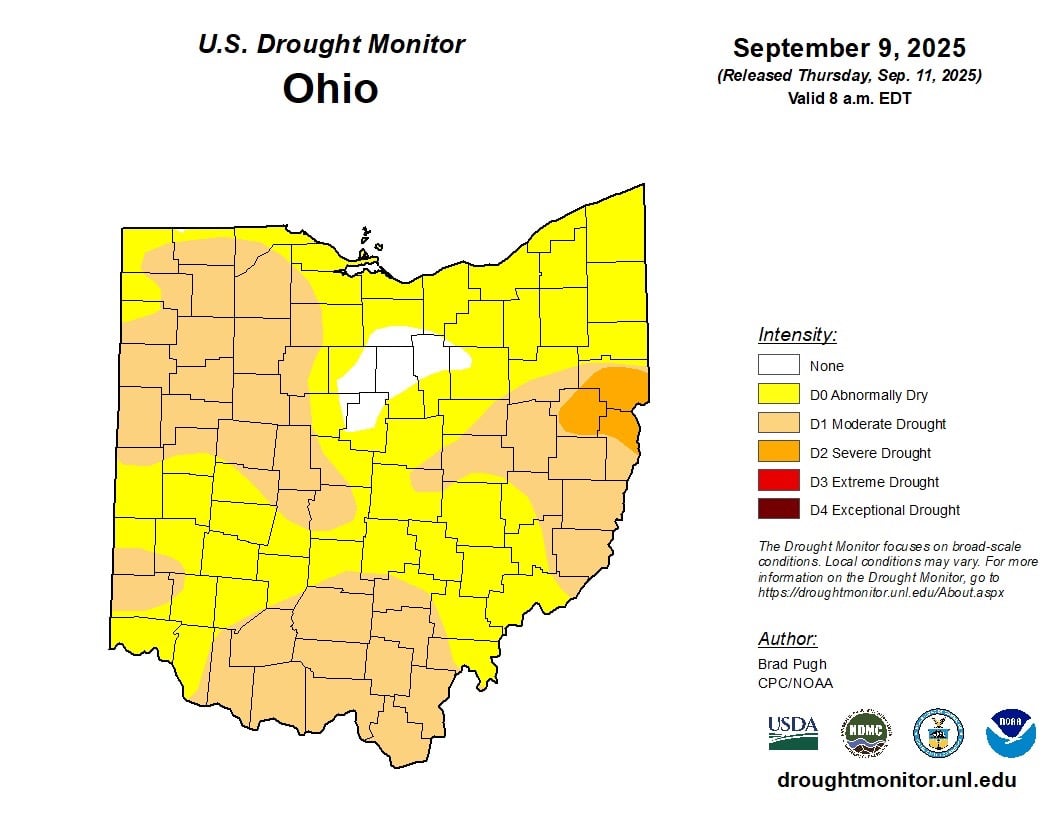

Central Ohio is in the middle of quite a dry spell. According to the latest U.S. Drought Monitor, 3.4 million Ohioans are living in areas currently affected by drought — a staggering 140% increase in just one week.

August 2025 went down as the driest August on record since 1895, with only 1.01 inches of rain for the month, which is about two and a half inches below normal. For comparison, the first eight months of the year actually leaned wetter than average, which makes this sudden flip to extreme dryness even more striking.

What drought means for Central Ohio

Drought in our region doesn’t always look like cracked earth and empty reservoirs, but it does ripple into daily life. Lawns and gardens are browning early, crops are stressed, and rivers and streams are running low. Longer-term, we could see impacts on water quality, agriculture, and even local recreation.

Across the Midwest, droughts in the past have disrupted barge traffic on rivers, reduced hydropower production, and hit farm yields hard. In Ohio, the most immediate concern is agriculture, where everything from soybeans to pasture grasses depends on late-summer rains that simply didn’t arrive.

The role of climate patterns

So what’s behind the parched conditions? Part of the answer lies thousands of miles away in the Pacific Ocean. Climate scientists point to the El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO), a recurring pattern that shifts sea surface temperatures and atmospheric winds.

This fall and winter, forecasters expect a La Niña to set in, with better than a 50% chance of lasting into early 2026. Historically, La Niña brings warmer, drier winters to the southern U.S. while the northern states — including the Ohio Valley — often see the opposite: cooler, wetter conditions. For Central Ohio, that could mean relief later this year, though the outlook is far from guaranteed.

Flash droughts: the new normal?

One of the biggest challenges in recent years is how quickly drought conditions can develop. So-called “flash droughts” intensify in a matter of weeks, catching communities off guard. Central Ohio’s sudden swing from a wetter-than-average January through August to the driest August on record is a textbook example.

What’s next?

Experts with NOAA’s National Integrated Drought Information System (NIDIS) stress that Ohio’s situation is serious but not yet as dire as the conditions out West. With La Niña brewing, there’s cautious optimism that fall and winter rains could replenish the region’s soil and streams.

In the meantime, residents can do their part by conserving water, supporting local farmers at markets, and keeping an eye on updates from the Drought Monitor.